Our Climate is a Nonlinear System

The climate is changing indeed. It has been changing for millions of years and will continue to change. The Earth’s climate system is highly nonlinear. The inputs and outputs are not proportional, change is often occurring abruptly, rather than slowly and gradually, usually in irregular intervals and durations and multiple equilibria are the norm. While this is widely accepted, there is a relatively poor understanding of the different types of nonlinearities, how they manifest under various conditions, and whether they reflect a climate system driven by astronomical forcings, by internal feedbacks, or by a combination of both. It is imperative that the Earth’s climate system research community grasp this nonlinear model if we are to move forward in the assessment of the human influence on climate.

The climate system incorporates for its formation, evolution, maintenance and variability major geological structures like the atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere , biosphere, and the cryosphere. The components

interact with each other or feedback (positive = self-reinforcement = negative self-regulation). Due to different reaction times of the components to external disturbances the climate represents a nonlinear system.

The climate system has a quasi-intransitive character, because the transitive, stable warm period has been interrupted since the Precambrian by several ice ages (intransitive phases). The climate of the earth is principally determined by the interaction of solar radiation with the atmosphere and the oceans. At a closer look it becomes evident that particularly number and complexity of those interdependences and again their feedback mechanisms are the key to the understanding of the climate system. These kind of actions that occur as two ore more climate components have an effect upon one another become more and more the focus of the climate system research and is worldwide intensively investigated. The absorbed radiation is already a variable at the surface, depending on the type of surface. Ice and snow covered surfaces reflect more - up to 90 percent of incoming solar radiation (albedo), and thus affect the radiation balance of high latitudes and high mountains. Is the earth's surface covered by plants, they have considerable influence on the reflectivity , in that context the destruction of huge forests areas and use for agriculture had an influence on the radiation balance and consequently the climate. The vegetation is also changing the evaporation profile and causes rainfall patterns - for example tropical rain forests produce much of the rainfall above its own areas by themselves.

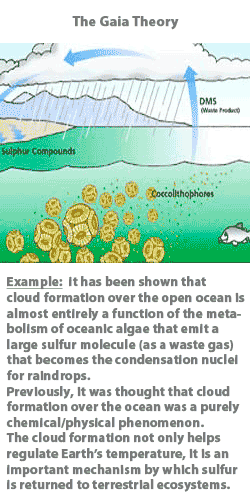

Plants influence the greenhouse effect by absorbing CO2 and partly binding them in stable structures like wood. Phytoplankton in the oceans is releasing dimethyl sulphide (DMS) which is oxidised in the atmosphere to form sulphuric acid (H2SO4) and becomes a nucleus of condensation for the formation of clouds. This is one of the cycles, which - according to the Lovelock's Gaia Theory (see left graphic) - life has a stabilisation effect on global temperature: Clouds reduce the solar radiation, the activity of phytoplankton is declining, therefore less DMS is released and fewer clouds are formed and the solar radiation again increases.

Geological processes throughout the earth history have altered the climate. For instance, the Indian monsoon was probably caused by the elevation of the plateau of Tibet. Geological processes also change the distribution of heat across the oceans, as with the shifting of continents ocean currents were occasionally disconnected or newly created. In that way the global deep current (the "global conveyor belt") was created only three to four million years ago when North- and South America came together. At the same time a warm, east-west maritime current was obstructed which in turn triggered the ice ages.

Another example of the complex interaction of various factors was the greening of the Sahara at the end of the ice ages. The fact that the Sahara has once not been a desert, has long been known, otherwise findings of giant underground aquifers, fish skeletons and petroglyphs were impossible to explain . Climatologist Martin Claussen could demonstrate that the advancing vegetation reflected less sunlight and altered air currents brought in rain clouds from the Atlantic. This feedback effect allowed the Sahara to become a habitat for animals and plants. When the rain stayed away later, according to some theories in the wake of the uplift of the plateau of Tibet, the Sahara again became a dessert as we know it today. But geological events may also have shorter-term effects on the climate. Some of volcanic eruptions that can be felt all over the earth, for example the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991, caused due to the release of the aerosol a temperature drop of 0, 5 degrees Celsius in the northern hemisphere of the earth.